The most

common refrain you’ll hear about the greatness of former players is something

along the lines of, “Sure, he dominated then, but there’s no way Player X would

be able to do that now. The players are just much more athletic now.”

Usually,

that’s an accurate assessment. Clearly, George Mikan would not lay waste to

centers today the way he did half a century ago, and if you’ve ever watch any

highlights of late 60s/early 70s basketball, it’s pretty clear that the game

today is played in a completely different gear.

There

are some players, though, for whom the opposite is true, that rather than

benefitting from the times, they were punished by them, and were they born 40

years in the future, their careers would be much, much stronger.

Take,

for instance, Al Tucker.

What if

he was born at the wrong time? What if, instead of coming into this world in

the midst of World War II, he arrived during Desert Storm? What would Al

Tucker’s legacy be, then?

You see,

Tucker never fit into the NBA in the late 1960s and early 1970s, not the way he

would have in the 1990s and 2000s. A 6’8” center at Oklahoma Baptist, Tucker

dominated the NAIA like no player before or since, three times taking his team

to the championship game, winning once, and earning tournament MVP twice.

You look

at his ridiculous numbers in college (the 30 points a game, the dozen boards),

and you see a heavy, a tough, a “big” man … and you’re not even close. Because

“Airline” Al Tucker was more than that, so much more.

He was

the kind of guy who could, while just messing around with his brother, invent a

play so integral to late 20th century basketball that to think of it

not existing would be impossible. The kind of guy who could toss passes that

would be talked of 40 years later. The kind of guy who could shoot a 3-pointer

like Dale Ellis on one end, then block shots like Marvin Webster on the other.

The kind of guy … wait, stop, let me go back a little further, let me tell you

the whole story of Albert Ames Tucker, Jr., member of the inaugural Seattle

Sonics.

Al

Tucker may have been born in 1943, but his basketball roots go back 20 years

before that, when his father, Al Sr., became the first black man to suit up for

Roosevelt High School’s basketball team. Senior’s abilities – developed as a

child with a tennis ball and a wooden basket nailed to a pole - led him to

Alabama State Teacher’s College, then the Harlem Globetrotters (or the Savoy

Big Five as they were also known for a time). Senior spent a number of years

traveling all across the country for the Trotters, including, believe it or

not, a game in January 1941 against the Enumclaw Merchants in Enumclaw (where

Brian Scalabrine’s red-headed grandfather, Obadiah Scalabrine, watched in awe

at the very end of the bench next to two cows and a three-legged sheep. Okay,

that part’s not quite true). The skills his son would show on a much larger

stage 30 years later were evident even then.

“I had a special basketball move,”

Al told a reporter in 1998. “It was a little deal where I’d come down just

beyond the foul line and when the defense moved in on me, I’d give a fake and

kind of swing over and slip away from ‘em. It worked so much they tried to make

a rule ‘round here. Said I was traveling. Truth is, I was just running in the

air. It was something they weren’t used to seeing and they said ‘Al, you are

pretty slick.’”

And so, “Slick” Al Tucker was born.

Less than five years later in Dayton, Ohio, Al Jr. came along, followed close

behind by a younger brother, Gerald (Al’s wife was Geraldine; whatever

creativity the Tuckers had on the basketball court did not, alas, extend to

baby-naming).

It was

no surprise when the Tucker boys showed an aptitude for hoops, what with their

father around to show them the way.

“When we

were coming up, we used to play at Blairwood Elementary and the city guys would

come out to play the Tucker boys,” Gerald said in 2005. “And we'd run 'em right

back down to the city."

After

dominating at Jefferson Township High School, young Al surely thought he’d have

a good shot at starring for the University of Dayton, but it didn’t work that

way, not for a young black man in the mid-1960s.

“Tom

Blackburn was the (Dayton) Flyers' coach when we got out of high school and

back then I don't think he wanted too many blacks on his team." Gerald

explained.

So, rather

than starring for his hometown college, Al was off to the College of Knoxville.

Tennessee. The early 1960s.

I think

you can guess where that was headed.

“We had what they called the Tennessee Theatre,” Al recalled in

2003. “And we would give the lady a dollar or whatever it cost to get in and

she said 'Sorry, we don't allow Negroes in.' Next thing they're going to call

the paddy wagon and take us to jail."

That essentially put an end to the College of Knoxville, and,

seemingly, to Al Tucker’s basketball career. He headed back to Dayton to play

for an AAU team with his brother and to await whatever fate destined for a

19-year-old black kid without a college degree in America.

In other words, nothing.

Luckily for Tucker, Gerald "Corky" Oglesby, a

scout from Oklahoma Baptist University, came to Dayton in 1963 to visit a

couple of prospects. While that didn’t pan out, he had heard that two other

young kids might be worth seeing. His eyes popped when he saw the Tucker

brothers in action, and Oglesby quickly got word to Bob Bass, OBU’s head coach,

that he’d found something special. Now he just had to convince Al Jr. that

Oklahoma Baptist wasn’t the College of Knoxville.

Gerald

remembers the encounter: "I was more outgoing than my brother and said,

'Let's go.' Al wasn't sure, but after Daddy talked to Corky, he told Al, 'Get

out of here and give it a try. You aren't doing nothing here but moppin' floors

at Concord City.' "

Junior agreed, and just like that, Al Tucker had taken his first

steps towards stardom.

An NAIA

school, Oklahoma Baptist University lies 30 minutes east of Oklahoma City on

Interstate 40 in Shawnee, Oklahoma, a town of no more than 30,000 people. (Coincidentally, three months after Tucker

arrived in town, Brad Pitt was born in Shawnee. It’s unknown if the young Pitt

ever made it to see one of Tucker’s games.)

But back

to our story. Al and Gerald arrived in town in the fall of 1963, not sure of

what to expect. After his experiences in Knoxville, no one would have begrudged

Al’s nervousness, especially when the Bisons went to play Southeastern

University and he got called “Buckwheat” by the crowd.

Tucker,

never one to retaliate with words let his skills do the talking, scoring 31

points in an OBU victory, his only acknowledgement of the painful taunts a

raised fist after every made basket.

Helped

by Coach Bass, who did his best to keep the Tuckers sheltered from racial

epithets and taunting – an impressive effort for a white coach in the 1960s

south – Tucker flourished at OBU, taking the team to the 1965 NAIA Tournament,

which he proceeded to dominate by scoring 25 points per game as the Bisons

advanced to the Championship before losing to Central State.

The next

year, Airline Al exploded, averaging 36.4 points per game in the tournament as

OBU claimed a massive 88-59 over Georgia Southern.

And,

before you dismiss the competition entirely, know this: In the three years

before Tucker’s three years at OBU, the NAIA Tournament featured a

tough-as-nails center from Grambling, who averaged 22.8 points per game,

including 27.4 his senior year. That center? Willis Reed. Or that other

tournament MVPs included Dick Barnett, Lucious Jackson, Zelmo Beatty, Lloyd

Free, all of whom posted solid NBA careers.

To further cement Tucker’s abilities, compare Reed’s 27.4 ppg as a

senior in 1964 to the numbers Tucker put up in his three years at the tourney:

25.0,

36.4, 32.8

Not bad,

right?

Tucker’s

final year proved to be frustrating, as the Bisons fell 71-65 to #1 seed St

Benedict’s despite Tucker’s 47 points in the championship game. And, yes, you

just read that Tucker scored 47 of his team’s 65 points, even though St.

Benedict’s knew they had to stop him, as Sports Illustrated observed:

“Coach Ralph Nolan figured he had to keep Tucker away from the

basket and started off playing him man-to-man. But Tucker beat that strategy.

When he was not firing in long-range jumpers he shuffled inside for hooks,

drives, reverse layups and stuffs. Tucker jammed in 47 points to earn acclaim

as the tournament's MVP, but not quite enough to give the Baptists a victory.”

I think it’s pretty safe to say that Tucker’s bona fides as a

college basketball player are solid. He spent three years at OBU, he was named

All-American all three years, took his team to the NAIA Championship all three

years, was named Tournament MVP twice, set a record for Tournament scoring that

stood for more than a decade, and generally dominated the crap out of everyone.

So, yeah, I think Al Tucker was a good college player.

But even having said all that, I haven’t said enough, because

when he wasn’t setting all sorts of crazy records, he was busy inventing the

most exciting play in basketball with his little brother, Gerald.

You see, legend has it that Al (6’8”) and Gerald (6’1”) were

messing around and came up with the idea that, hey, wouldn’t it be neat if

Gerald lofted the ball up in the air and Al slammed it through the basket?

Yes, in addition to all the accolades, in addition to the

tournament glory, Al Tucker invented the

alley-oop.

The play

would gain greater acclaim with David Thompson at NC State a few years later,

but it is generally accepted that it was Tucker & Tucker that first came up

with the idea. And while that sort of thing is generally tough to accept as

hard fact, if you were to brainstorm about the perfect scenario for creating the

alley-oop, wouldn’t a 6’8” dunking machine and his younger, smaller

passing-oriented brother make a bit of sense? When you throw in that their dad

was a former Harlem Globetrotter, well, it just makes a whole lot of sense.

Add it

all up and you can see why an expansion team from Seattle was so eager to

select Al Hunter with the 6th pick of the 1967 NBA Draft.

PART II

– After Graduation

In the

spring of 1967, the Seattle Sonics and the San Diego Rockets flipped a coin to

determine the teams’ placement in the upcoming NBA draft. With a smidgen of

luck, the Sonics won the toss, giving the right to select 6th, and

consigning the Rockets to 7th.

(Quick

tangent: See Vancouver fans, this is how it can work. Even though you don’t get

to pick first, you can still keep your team for 40 years before David Stern

rips your heart out.)

Anyhow,

the Sonics’ GM, Don Richmond, was faced with a bevy of possibilities with that

pick: Kentucky’s Pat Riley, New Mexico’s Mel Daniels, North Dakota’s Phil

Jackson, even local product Tom Workman of Seattle U. Instead, Richmond went

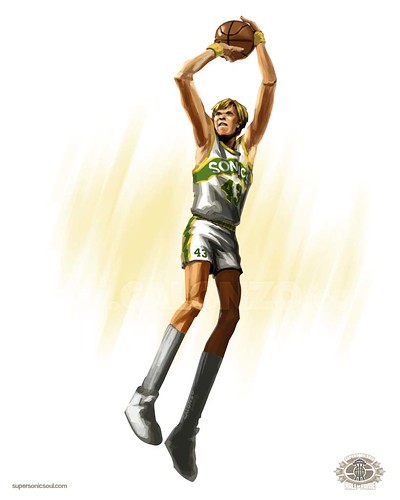

with a 6’8” center/forward from OBU, Al Tucker. But, of course, you already

knew that.

Tucker’s

speed and outside shooting, to go with his height, made him an asset to the

young team. The Sonics planned on being a team that put up a lot of shots that

first season (and succeeded, as they finished third behind only the Lakers and

Sixers in points per game); with Tucker, they had a “speedy forward to fill the

lanes on the break,” as SI put it.

Tucker

began the season in fine fashion, and as you can

see from this yellowed clipping from the Seattle PI, he managed 10 points

and six rebounds in his first game in a Sonics jersey. (Note that the Warriors

had their way in the paint, grabbing 81 (!) rebounds, although, with 131 missed

shots between the two clubs, they certainly had their opportunities).

The

rookie forward didn’t waste his time in contributing to his rookie team, pacing

the Sonics with 18 points in only his sixth NBA game, then following that up

with the team lead in rebounds in three consecutive November contests.

Tucker

maintained his contributions throughout the season, going on to lead the team

in points seven times, including a 35-point night against the Lakers on

December 10, and 28 against the Warriors in March. By the time the season

ended, Tucker had finished with 13 points and 7.5 rebounds a game and the third most total rebounds on the club.

Admittedly, his advanced numbers were a bit pedestrian (he finished in the

middle of the team in Offensive Win Shares and 8th in PER), but for

a skinny rookie from an NAIA school, he came through just fine.

Voters

for the All-Rookie Team felt so as well, deeming Tucker’s performance worthy of

a starting spot on the squad, where he joined fellow rookie Bob Rule, Walt

Frazier, Phil Jackson, and Earl Monroe.

His

career underway, a All-Rookie Team trophy on his mantle, if you were Al Tucker,

the summer of 1968 had to be a pretty good one, no? You have to imagine he came

back to Dayton to see the family, talk with his dad about his exploits … and

you have to think that Al Tucker Sr. must have had a whirlwind of emotions. His

eldest son was experiencing everything he, the father, had been denied 20 years

before. The steady paychecks, the notoriety … Al Sr. missed out on that simply

because he was black. But now everything was different. And while Geraldine was

probably more concerned about her younger son, Gerald, being off in Vietnam

experiencing God knows what terrors, Al Jr.’s success had to have been a

blessing to both parents.

Strangely,

though, that summer would prove to be the last one in which Al Tucker Jr.’s

basketball career would have any sort of upwards arc. In the next four years he

would play for six teams, be waived multiple times, and finally call it a

career at the age of 28.

What

happened?

Part III

later today

Part III

The

aftermath

In Al

Tucker’s last game as a Sonic, he registered 0 points and 2 rebounds. His

denouement came in a 119-112 win over Atlanta; he spent the last three quarters

of his Sonic career on the bench as a spectator in a frustrating end to a

frustrating sophomore season.

Who

knows why Coach Al Bianchi chose to sit Tucker – it could have been the 12

points he allowed Lou Hudson to score in the first period, or (more likely) it

could have been that he had been traded to the Cincinnati Royals for John

Tresvant.

The

reasoning for the trade, as viewed by the Times’ Georg Myers, was simple – the

Sonics needed to get tougher and “Supertwiggy,” as Myers and thousands of Sonic

fans had dubbed Tucker, wouldn’t cut it anymore.

“The

principal difference distinction between Tucker and Tresvant,” wrote Myers, “is

that John has the heft and the temperament to be authoritative and aggressive,

especially on defense.”

A

withering portrait of Tucker, to be sure, and one echoed by an anonymous scout

40 years later. Tucker was “blessed with talent but not a lot of motivation,”

the scout told the Times’ Bill Reader in 2006 (and if that scout isn’t Henry

Akin, I’ll eat my keyboard).

Ironically,

less than a year before, in June of 1968, Myers had nothing but good things to

say about Tucker.

In the

afterglow of his All-Rookie accolade, the rookie admitted to Myers his first

NBA season was “tougher than I thought it would be. And I knew it was going to

be tough.”

Tucker

explained to Myers that he learned in his first year that the major difference

between college and pro ball was that he was on his own.

“Nobody

is looking after to you except yourself,” Tucker explained. “The coach isn’t

going to hold your hand.”

Myers’

fawning piece went to great lengths to show how Tucker was going to bulk up

over the summer, but, more importantly, that he understood what it took to be a

successful NBA player.

How,

then, did this strong relationship between young player and team fall apart so

quickly?

---

When the

Sonics ran off a win against Boston in mid-January, Tucker’s strong effort was

counterbalanced by a comment in the Times that he had been a “major

disappointment most of the season.” Almost every story the paper ran after the

trade was consummated held some reference to the “slender” Tucker, how Seattle

was a “tougher” team now that Tresvant was on board, how the Sonics were better

at rebounding and defense, and so forth.

It’s a

puzzler, isn’t it? On the one hand, you have Airline Al Tucker, hero to

thousands in Shawnee, Oklahoma, where 40 years after he led OBU to a national

championship he’s revered by one and all, not just as an athlete, but as a

friend.

On the

other, you have Al “Supertwiggy” Tucker, who apparently wasn’t interested in

utilizing his “God-given” talents (a useless phrase if there ever was one).

Consider,

for a moment, the obstacles Al Tucker overcame to become an NBA player:

-

Not

recruited by his hometown university because he was black

-

Forced

to play at an NAIA school

-

Endures

racial taunts by opposing fans and ignores them

-

Battles

people much heavier than he as a center, and dominates the competition, earning

three All-American awards in three years

-

Comes

up huge in crucial games, including 47 (!) points in the NAIA championship his

final year at OBU

-

Rebounds

like no one before or since a OBU

And

we’re supposed to believe he just showed up at the Seattle Center Coliseum and

quit trying? That he just took the money and ran? That he wasn’t capable of

grabbing rebounds all of sudden?

Further,

if we’re to swallow the notion that Tucker just didn’t care about anything,

then explain why he spent the summer after his rookie year studying chemistry

at Oklahoma Baptist? And if the idea that Tucker was a hindrance to the team

were true, if Tucker was such a disastrous underachiever, why would Bianchi go

with him for the entire 24 minutes of the second half just two weeks previous,

a victory over Cincinnati?

I think

the real answer is that the Sonics were falling apart. The team had gone 2-18

from mid-December until late January, and even though they rattled off three

consecutive wins to end that streak of misery, the front office and coaching

staff obviously had to do something. In the manner of the time, clichés ran the

day and the Sonics needed to get “tougher.” Tucker, a 190-pound small forward

with glasses, an art lover who loved sculpture, was deemed expendable.

Which is

why, on January 31, 1969, Al Tucker found himself a Cincinnati Royal and John

Tresvant found himself a Seattle Supersonic.

In a

way, it was a homecoming for both players. Tucker, a native of Dayton, now

found himself playing less than an hour’s drive from his parents’ home, while

Tresvant, the former Chieftain, would now be able to play in front of his

college classmates in Seattle.

Bizarrely,

the two would meet on the court less than a week later when the Sonics and

Royals faced off in Seattle. The Sonics, led by Lenny Wilkens’ 32 points and

Tresvant’s 19 rebounds, knocked off Cincy 102-97, although Tucker had some

small revenge with 13 points, including 11 in a short span of the second period.

“As long

as we won,” Coach Al Bianchi said after the game, “I

was happy to see Al have a good game.”

And with that, Al Tucker’s voyage through the nether

regions of professional basketball circa 1970 began.

---

Up first, Cincinnati. With Oscar Robertson, Jerry

Lucas, and Tom Van Arsdale, the Royals had a strong roster, but were in the

midst of a seven-year absence from the playoffs. Fans didn’t exactly flock to

Cincinnati Gardens to take in the games, either; the team ranked last in

attendance for the ’68-’69 campaign.

Still, considering what Al Tucker was leaving behind,

it wasn’t that bad of a deal. The Sonics were even worse than the Royals, and

with Lucas averaging nearly 20 boards a night and Connie Dierking almost 10,

Cincinnati didn’t need any help grabbing rebounds. They needed scoring, and the

slender small forward from Dayton seemed to fit the bill.

It didn’t work, though. 27-25 when they acquired

Tucker, the Royals went 14-16 down the stretch, finished out of the playoffs,

and waived their new acquisition at the end of the season in an ignomious end

to Tucker’s return to Ohio.

June ’68 to

June ’69; America switches from Lyndon Johnson to Richard Nixon, and Airline Al

switches from All-Rookie Team to nobody.

---

Tucker spent the summer wondering where his future

would take him, before landing that October in Chicago for the woeful (29-53

the previous year) Bulls. Chicago had hired a new coach, Dick Motta, to replace

the outgoing Johnny Kerr, but it made little difference in the club’s fortunes.

By the time January rolled around, the Bulls were well

below .500 and in need of a change. So, figuring that Tucker – a bit player

averaging 7 points in 17 minutes off the bench – was expendable, they Chicago sent

him to Baltimore for Ed (father of Danny) Manning.

Unlike Tucker’s previous stops in Chicago and Seattle,

the Bullets were a good club, and led by fellow draftee Earl Monroe and the

previous season’s MVP, Wes Unseld, Baltimore was primed to improve upon their

4-0 flameout against the Knicks the previous year.

Al Tucker, however, was not to be a crucial part of

that experience, though. While he managed to get his first taste of playoff

action in Baltimore’s 4-3 loss to New York, the eventual NBA Champions, it was

only five minutes in four games. Strictly mop-up duty.

Now 27, Tucker returned to Baltimore the next year,

hoping to get some more action in what was his fourth NBA season. On his fourth

team in as many years, the young man from Dayton must have been wearied from

his nomad existence, frustrated at his lack of success.

31 games in, the Bullets had seen enough, waiving him

and ending Tucker’s NBA career. The only thing left for him at that point – 27

years old, college superstar, professional washout - was the ABA.

So that’s where he went.

Part IV – The ABA and The End

His NBA

career in disarray, Al Tucker was at a crossroads. Was he a professional

basketball player? Everything he had worked for in the past decade – past two

decades, really – was seemingly for naught. Sure, he had made it to the NBA,

he’d been named a member of the All-Rookie Team, but four different franchises

had dumped him in the past four years.

Did he

really need this anymore? At that point, fate intervened and reunited Al Tucker

with someone from his past.

Coach

Bob Bass, who had been such a friend to Tucker back at Oklahoma Baptist, had

been named the head coach of the Floridians (they didn’t bother with the

“Miami” at that point) in the ABA in mid January, and had converted an 18-30

team on his arrival into a more potent force.

Still,

Bass needed some extra firepower to go with Mack Calvin and Larry Jones, and

his prior relationship with Tucker must have held some sway, as the Floridians

picked up Airline Al for the final 14 games of the season.

Tucker

delivered, averaging 12 points in only 24 minutes, and by the time the playoffs

rolled around, Tucker was a crucial part of the rotation.

The

Floridians lost in the first round to Dan Issel and the Kentucky Colonels, but

Tucker tallied the fifth-highest minute total on the team in the post-season,

and, just as it did 10 years before in Shawnee, the future seemed bright for

Tucker and Bass.

In the

1971-72 season, Tucker returned to Miami and played in all but 3 games for the

team, knocking down 30 of 82 3-pointers for the best percentage on the team,

and averaging his usual 18 or so points per 36 minutes.

Something

happened in the second half of the season, though, and Tucker seemingly wound

his way into Coach Bass’ doghouse, as the 28-year-old only played in three of

the team’s four playoff games, and even then for only minor action. While the

year before he was one of the five regulars in the playoffs, in 71-72 Tucker

played the next-to-fewest among the Floridians.

After

the Floridians were knocked out of the post-season in the first round (again),

the team folded, and in June Tucker was picked in the third round of the ABA’s

dispersal draft by the Denver Rockets.

He never

played another game.

---

And

that’s all we know about Al Tucker. For the rest of his life, he’s invisible,

on the internet, anyways, until May 2001, when he was struck by a brain

aneurysm and died in Dayton, Ohio.

Four

years later, his younger brother, Gerald, who had teamed up with Airline Al at

OBU so many years before, still wasn’t over his brother’s death, forcing him to

cut short an interview with the Dayton Daily News.

We’ll

let John Parrish, longtime member of the Oklahoma Baptist family, and author of

a book which details even more the story of Al Tucker as it relates to OBU to

have the final word about Airline Al.

"We've

got three trophy cases filled with Al's things,” Parrish told the Dayton Daily

News. “Everybody remembers him. The last time he was out here in 1999, we were

walking around the campus and went into the cafeteria.

“An old guy

was in there and I said, 'You remember who this is?' And he just grinned, 'Oh

course. Nobody forgets Al.’”

References: